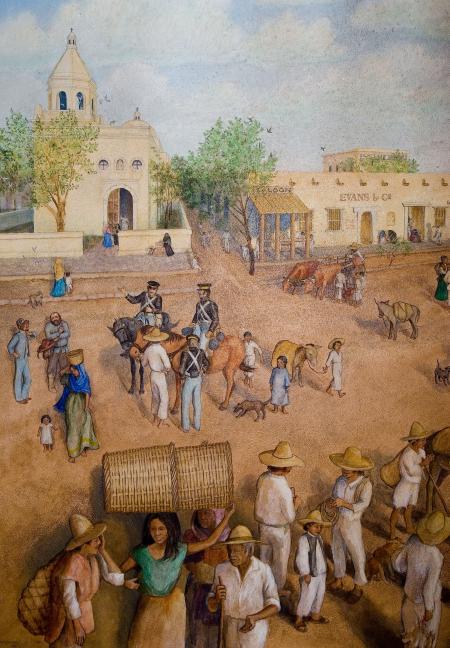

José Antonio Navarro was an influential political figure during the momentous 55 years (1810–1865) when Texas’ destiny was forged. Navarro served in Texas legislatures under Mexico, the Republic of Texas, and the state of Texas. In addition, he served on the committees that wrote the first two Texas constitutions in 1836 and 1845.

Although a prominent, influential leader, Navarro was not a professional politician. As a young man he learned the merchant trade, the occupation of his father. Factories from the United States and Europe sent ships loaded with merchandise to New Orleans, where Navarro arranged to import books, cloth, clothing, wine, sugar, rice, and coffee.

Navarro also earned a living through land investment. During the 1830s, he purchased more than 50,000 acres of ranchland at a price of pennies per acre. Because thousands of people were immigrating into Texas, the demand for land increased. Navarro sold portions of his land holdings for up to three dollars per acre. His San Antonio rental properties also produced income.

His wife Margarita de la Garza was also a native of San Antonio. Between 1817 and 1837, she bore four sons and three daughters. Numerous descendants live in and around San Antonio, with many more scattered throughout the country.

Did You Know?

- Navarro was one of only two native-born Texans to sign the Texas Declaration of Independence in 1836.

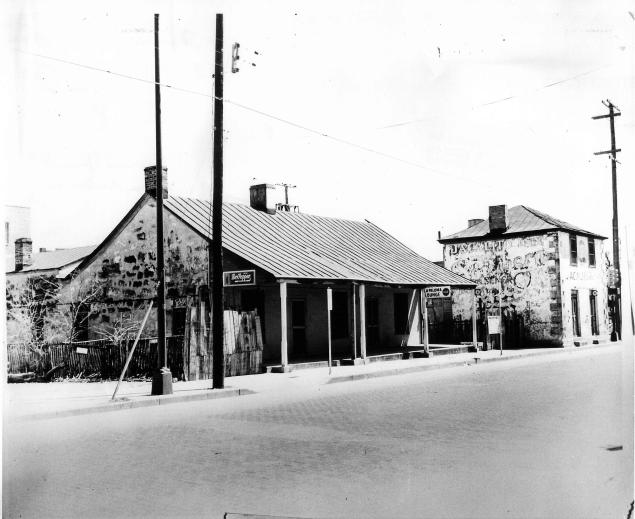

- Casa Navarro is the last remnant of the historically Mexican west side of San Antonio, known as Laredito (Little Laredo), and it is located on Laredo Street, a vestige of the Camino Real (King’s Highway).

- The home is a rare example of adobe and caliche-block architecture and is among the oldest adobe structures remaining in San Antonio. The oldest building on the property is the adobe kitchen, built ca.1832.

- Casa Navarro staff is capable of demonstrating adobe-making techniques, by request in advance and based upon availability.

-

Image

Tejanos relied heavily on Texas’ natural environment to supply them with materials for building homes. Many homes built by Tejanos are known as jacales, rectangular structures with walls made from trimmed mesquite limbs and filled with mud or plaster in between posts. Roofing was made from reeds, straw, or thick grass, depending on availability, and flooring was typically compacted dirt depressed only a few inches below the threshold. Jacales took little money to build, lasted long periods of time, and were efficient in cooling and heating throughout the year.

Margarita de la Garza, wife of José Antonio Navarro, described living in a jacal made of palos y cascara (sticks and bark) with her mother into adulthood. In comparison, Navarro was raised in a casa mayor (fine home) constructed of limestone block, that sat only a few blocks away.

Tejanos of privileged backgrounds utilized the environment in a different manner, opting to make their homes from adobe or stone cut from nearby quarries. Adobe home construction in Texas was a craft perfected over several centuries by Spanish and Native Americans throughout Northern Mexico and Texas. A varied mixture of clay, topsoil, grass, powdered lime, and water was placed into rectangular forms and left to dry in the sun. The dried bricks were stacked to make walls one-story high and typically measured 2–3 feet in thickness. The adobe bricks were then covered with a coat of plaster and whitewash made from cactus mucus and hydrated lime to protect them from the elements.

In 1832, Navarro purchased the property at the corner of Laredo and Nueva Streets, now Casa Navarro State Historic Site. He did not reside at the property regularly until his home and the two-story mercantile building were completed in the mid-1850s. All three buildings on-site are examples of adobe architecture common in San Antonio during the mid-19th century.

The main home was originally built one room deep and one story in height, common for adobe construction, and likely had a vaulted ceiling with cedar shingles for roofing, similar to the mercantile and kitchen buildings. Distinctly Texas Colonial in styling, the symmetrical positioning of the doors, windows, and porches of the main home provided adequate air circulation and shade during the summer months while the fireplaces and earthen bricks kept the home warm in the winter. Three rooms were added to this building at a later date, but designed to match the pre-existing styling of the home.

Also in Texas Colonial architectural styling, the mercantile building is a rare example of a two-story adobe structure incorporating cut limestone quoins. The building likely functioned as a storefront and warehouse for a business owner Navarro rented to during the time, and was later utilized as an inn, restaurant, bar, and grocery store by the residents of Laredito. Access to the second floor of the building was through a stairway located on the eastern exterior wall.

The eldest of the site buildings is a small adobe structure built in the 1830s and later expanded to the north and south in the 1850s. This building was likely used as a kitchen and housing for servants during Navarro’s time. The floor of the building was compacted dirt, unlike Navarro’s home and mercantile building, which had wood flooring.

Although not much is known about the contents and furnishings of Navarro’s home in Béxar, it is likely that the homes were modestly decorated like those of many other Tejanos. Rudimentary cabinetry provided space for clothes, cookware, and household items, while furniture was likely simple in appearance and functionality. Tejanos valued homes not necessarily by their contents, but rather as spaces where traditions, culture, and folkways could be passed on between generations. Navarro, the aging Tejano statesman, was surely delighted by the many guests and family members that visited him regularly until his death at the home in 1871.

-

Image

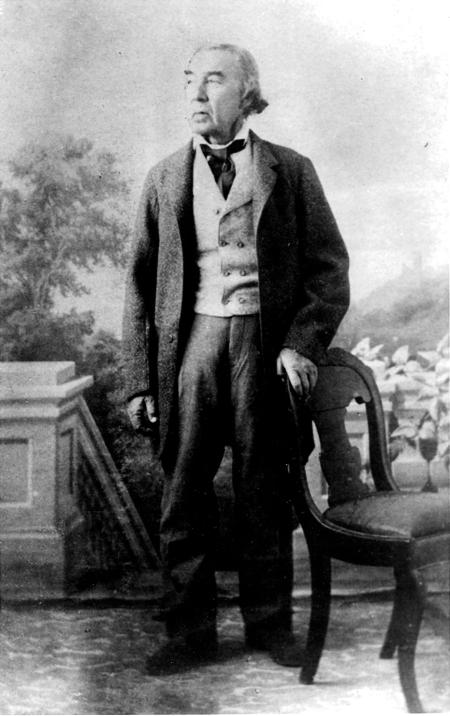

José Antonio Navarro was born in San Antonio on February 27, 1795 to a family of means and political connections. He was the eighth of 12 children, six of whom lived to adulthood. His father, Don Angel Navarro, was a self-made man from Corsica who went from being a runaway and servant to becoming a successful merchant and Alcalde of San Antonio (a political position that included being mayor, sheriff and judge). Navarro’s mother, Maria Gertrudes Ruiz, was a native of San Antonio and of aristocratic descent.

Navarro’s father died in 1808, and at the age of 13, he returned from school in Saltillo, Mexico to help support the family. When he was 18, he fled to Louisiana to avoid the Spanish rule in San Antonio, returning home to Bexar three years later. On his return, he found his mother and family nearly destitute and immediately set out to find work to support them. Navarro was largely self-taught, and he became a successful merchant, rancher, politician and land investor. He married Margarita de la Garza y Flores, a native of San Antonio, and they had four sons and three daughters.

Before Texas independence, Navarro was elected to both the Coahuila and Texas state legislature and to the federal congress at Mexico City. He supported Texas statehood in 1835 and embraced the idea of independence the following year. Navarro was one of the three Mexican signers of the Texas Declaration of Independence along with José Francisco Ruiz and Lorenzo de Zavala. He was elected to the Texas Congress as a representative from Bexar and sought to advance the rights of Tejanos, whom many Anglo-Texans held in contempt after the Texas Revolution.

In 1841, Mirabeau Bonaparte Lamar, president of the Republic of Texas, organized the Santa Fe Expedition. His plan was to incorporate eastern New Mexico into the Republic of Texas. Navarro did not favor the plan, but against his better judgment was persuaded by Lamar to remain as a commissioner of the expedition.

The Santa Fe Expedition ended in disaster; Navarro and the other members of the expedition were taken prisoners by the Mexican authorities. Many did not survive the grueling and punishing 2,000-mile march to Mexico City. Navarro underwent intense interrogations by Mexican authorities and was offered freedom and a government position if he would renounce his allegiance to Texas. He steadfastly refused to betray his homeland and was convicted of treason and sentenced to death.

The Military Supreme Court commuted his sentence to life imprisonment. Santa Anna had Navarro transferred to the most dreaded prison in Mexico — the infamous San Juan de Ulúa in the Port of Vera Cruz. Navarro spent four years in the brutal dungeons, enduring miserable and torturous conditions. In 1844, Santa Anna was overthrown and in early 1845 Navarro managed to escape aboard a ship from Vera Cruz to Cuba. From Cuba, he sailed to New Orleans and then Galveston, arriving back at his San Geronimo ranch on February 18, 1845.

At 50 years of age, Navarro was finally home. He was welcomed as a true hero and earned immense respect from the people of San Antonio and Texas. Navarro County, Navarro Street and numerous public schools are named in honor of his heroic patriotism and leadership.

For the next 26 years, Navarro’s leadership and passionate quest for liberty significantly influenced the course of Texas history. He was the sole Tejano delegate to the Convention of 1845 determining the United States’ annexation of Texas, which he supported. He also contributed to the Constitution of 1845, the first state constitution. He was subsequently twice elected to the state Senate, but retired from the legislature in 1849.

During his retirement, Navarro wrote several historical and political articles for the San Antonio Ledger. In 1854, Navarro publicly opposed the “Know Nothing Party,” officially known as the American Party. The group felt threatened by immigration from Catholic countries; consequently the party was anti-Catholic and anti-immigration. It operated as a secret society and in response to inquiries about their activities the members would repeat such denials as “I don’t know, I don’t know anything,” resulting in their nickname. The party gained major victories in Texas and San Antonio, and Navarro helped to create an informed electorate that delivered defeat of the Know Nothing Party at the polls in Texas in 1855.

José Antonio Navarro died at his home on Laredo Street, now the Casa Navarro State Historic Site, on January 13, 1871.

-

As the president of Texas, Mirabeau Lamar had a grand vision for expanding the Republic into New Mexico. He would send an expedition to Santa Fe in order to convince the people of New Mexico to join Texas.

Lamar selected José Antonio Navarro as a commissioner for the quest. He knew that Navarro was a respected statesman, but beyond that he was also a prominent businessman and an expert on Mexican law. Navarro also spoke Spanish and could help negotiate with the New Mexicans.

Navarro had every reason to reject Lamar’s overture. The 46-year-old father of seven had several growing business interests. He was also an important civic leader in San Antonio. His health was uncertain, and a childhood leg injury promised to make the long journey very difficult for him.

Yet Navarro knew that he must accept. He had seen the promise of the Texas Revolution turn sour for many Tejanos. They had joined the fight for independence but now were increasingly targeted as enemies by vengeful Anglos. Navarro’s service would prove Tejano loyalty to the Republic. He said, “My participation would serve…to avoid a crisis among my fellow citizens.”

The ill-fated Texan-Santa Fe Expedition left Austin in the summer of 1841. Navarro traveled with 320 soldiers and 21 ox-drawn wagons. The wagons were piled high with $200,000 in trade goods—the equivalent of $5.5 million today.

The expedition was a disaster from the beginning. Water was scarce, and the group got lost on the high plains. Several men deserted and some died on the way. Finally, after a punishing three-month journey, the bedraggled group arrived in New Mexico. They were met by an overwhelming force of 1,500 Mexican soldiers. The Texans had no choice. They surrendered without firing a shot.

The prisoners were marched 1,500 miles to Mexico City. Waiting for them was Santa Anna, anxious to exact revenge for his defeat at San Jacinto. Santa Anna was especially eager to punish Navarro, who he considered a traitor. After vigorous diplomatic efforts by the United States, Mexico finally agreed to release the Texans and send them home. Yet, Santa Anna refused to free Navarro. He was convicted of treason and sentenced to death.

But Santa Anna offered Navarro a deal: if he renounced Texas, he would be forgiven and allowed to take a prominent government position in Mexico. Navarro refused. He remained in prison for more than three years, never knowing what day he might be taken out and shot. Finally, with the help of sympathetic Mexicans, he escaped and returned to Texas.

Navarro arrived home in mid-winter, 1845. He was just days from turning 50. He was considerably grayer and in failing health. Texans welcomed him as a great hero. He had proved his valor and courage as a prisoner of Santa Anna. Even under the threat of death, he remained a true Texas patriot, stating, “I have sworn to be a free Texan, and I shall never forswear.”

-

Tejano ownership of slaves was not uncommon, but Tejano attitudes toward slaves and slavery were complex. While José Antonio Navarro owned slaves, he and his family reflected the conflicting attitudes toward slavery in both Mexico and the United States as Texas became the state it is today.

Mexico’s recent independence from Spain was based largely on the ideas of the enlightenment, which clashed with the practice of slavery. Both leaders of the movement for Mexican independence, Father Miguel Hidalgo and Agustin de Iturbide, made calls for social equality and an end to enslavement.[1] Instead of slavery, Mexico’s economy in the 19th century relied heavily on a system of debt peonage in the forms of debt labor or indentured servitude.[2]

Angel Navarro, father of José Antonio Navarro, used this system to travel to New Spain from Corsica in 1762. Before arriving in Bexar (San Antonio), Angel sought work with Don Juan Antonio Agustin in the mining district of Vallecillo. Eight years of work in the silver mines paid for his passage across the Atlantic Ocean. In 1777 Angel was freed and came to Bexar as a merchant, living with others from Corsica. By 1781, the elder Angel had purchased a lot and dwelling in Bexar and was elected to the city council.[3]

Most Tejano elites knew of the practice of slavery from the cotton markets of New Orleans. This led many of them to advocate for cotton production in the state of Coahuila y Tejas to lure wealth, people, and economic activity to the sparsely populated Mexican frontier. As a result, these Tejanos sought to protect the practice of slavery in Texas, upon which cotton farming relied heavily.[4] It was not uncommon for families of this group to own slaves in the colonial period. Although the number of families holding slaves was small, it was a vital connection between Tejano elites and American cotton growers immigrating to Texas.[5]

José Antonio Navarro, as a legislator in the state of Coahuila y Tejas, introduced a bill that ensured foreign contracts be honored. The bill, known as the Law of Contracts, allowed for slaves to enter Texas as indentured servants under contract of their former owners to whom they would repay their debt in labor.[6]

During this period, José Antonio Navarro contracted with a woman named Meralla, who acted as his criada, or servant. In 1834, Navarro contracted with John W. Smith for Meralla’s services, for which he was paid 24 pesos. There was a possibility Navarro owned Meralla outright or that she was an indentured servant, much like his father when he immigrated to New Spain. [7]

Texas independence from Mexico and the Constitution of the Republic of Texas guaranteed that slavery would continue in Texas from 1836 onward.[8] Protections to slaveholders and the slave trade in the republic pushed the number of slaves in Texas to at least 30,000 by the time Texas became a state in 1845.[9]

Like other Tejanos, the Navarro family had a complex relationship with their slaves. José Antonio Navarro’s tax records indicate that he owned six to nine slaves between 1856 and 1864. Census data shows Navarro owned one slave, a 12-year-old male, as early as 1850. The young man, named Henry, lived and worked at Navarro’s San Geronimo Ranch, northeast of San Antonio, but little is known about the conditions in which he and Navarro’s other slaves worked and lived. The ranch’s operations did not rely entirely on slave labor since three laborers from Mexico and two of Navarro’s sons worked for him.[10]

Patsy Navarro first appears in the 1860 Census Slave Schedule alongside Henry Navarro, and the two are listed in the 1870 census as spouses and heads of a household. In 1856 Henry and Patsy Navarro’s daughters, Jesusa Patsy and Maria Patsy, were christened into the Catholic Church. Margarita de la Garza, Navarro’s wife, is listed as the girls’ godmother. Four years later another daughter, Rosa Navarro, was christened.[11]

By 1860, Navarro’s ranching operations had moved primarily to his Atascosa County Ranch where six slaves lived and worked, including Henry Navarro, who was 22 at the time. Six others resided on the Navarro ranch—three women ages 21 through 30, and three children ages 1 through 7. Given the nature of ranching operations, it is likely Navarro’s slaves dedicated most of their time to basic farm tasks including raising livestock, planting, harvesting, and other household chores. The ranch produced corn, butter, and sweet potatoes and had 100 milk cows, 12 oxen, and 200 swine at the time.[12]

The admission of Texas to the United States would strongly impact the conflict over slavery and its expansion westward, leading to the secession of slaveholding states and formation of the Confederate States of America. Following the implementation of the Emancipation Proclamation in Texas on June 19, 1865, it is likely that Navarro’s former slaves, now freedmen and women, stayed on the ranch to work for wages or shares of crops, meat, and other farm products.[13] Henry Navarro did not remain a hired worker for long; records indicate he lived on the ranch with his family for only two to three years afterward.

By 1868 Henry had managed to acquire four horses, 20 cows, and a considerable amount of farm equipment. The following year Henry became a landowner by acquiring 160 acres of land in Atascosa County through a preemption grant, which allowed Henry to claim land in the public domain and gain a title. In 1870, the census listed Henry as the head of a 10-person household where he and Patsy raised five children, Henry Jr., Lucinda, Mary, Edmund, and Rose, ages 3-11. Also residing in the Navarro household were Malie Richards, a 50-year-old housekeeper from Arkansas, Susan Ford, age 18, from Arkansas, and Sarah Cox, age 13, who attended school.

Henry and Patsy had an ongoing relationship with the Navarro family following emancipation. Henry and his family continued to increase their landholdings to 520 acres by 1885, 277 acres of which were sold to him by José Antonio George Navarro and Sixto Navarro. Because Henry was illiterate, Abraham G. Martin, Charles Flores, and Fernando Hernandez provided assistance with the grant certifying that Henry was a credible and trustworthy citizen of Atascosa County.

In 1884, Henry and Patsy donated an acre of land to the Methodist Episcopal Church in Atascosa County that would be used for a church, school, and cemetery known as the Brite-Navarro Cemetery.[14] Patsy Navarro was buried in that cemetery in 1888. Henry Navarro died in San Antonio in July 1904, and is presumed to be buried in the Brite-Navarro Cemetery along with Patsy and several of their children.

Further reading

- African Americans and Race relations in San Antonio Texas, 1867-1937, Kenneth Mason, Taylor and Francis Publishers, 1998 Studies in African American History and Culture Series

ISBN #’s 0815330766 and 9780815330769 - World of a Slave: Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the United States, Volumes I & II, Martha Katz-Hyman and Kym S. Rice, Greenwood Press, 2011

ISBN #978-0-313-34943-0 - Los Brazos de Dios: A Plantation Society in the Texas Borderlands: 1821-1865, Sean M. Kelley, Louisiana State University Press, 2010

ISBN #978-0-8071-3687-4 - Homesteads Ungovernable: Families, Sex, Race, and the Law in frontier Texas, 1823-1860, mark M. Carroll, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2001

ISBN # 0-292-71228-6 - Seeds of Empire: Cotton, Slavery, and the Transformation of the Texas Borderlands, 1800-1850, Andrew J. Torget, University of North Carolina Press, 2015

ISBN # 978-1-4696-2424-2 - Women on the Texas Frontier: A cross Cultural Perspective, Ann Patton Malone, Texas Western Press, University of Texas at El Paso, 1993

ISBN # 0-87404-130-9 - The article Between Black And White: Race and Status among the Tejano Elite in 19th Century San Antonio, Roque Planas, University of the Incarnate Word’s Journal of the Life and Culture of San Antonio. Free online at http://www.uiw.edu/sanantonio/blackandwhite.html.

- An Empire for Slavery: The Peculiar Institution in Texas, 1821—1865, Randolph B. Campbell, LSU Press, 1991

ISBN # 0807117234 and 978-0807117231

[1] Andrew J. Torget, Seeds of Empire (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015), 70-71.

[2] Raúl A. Ramos, Beyond the Alamo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 91-92.

[3] David McDonald, José Antonio Navarro (Denton: TSHA Press, 2010), 13-15.

[4] Torget, Seeds of Empire, 71-72.

[5] Ramos, Beyond the Alamo, 92-93.

[6] McDonald, José Antonio Navarro, 80-83. Torget, Seeds of Empire, 131-133.

[7] McDonald, José Antonio Navarro, 118.

[8] Torget, Seeds of Empire, 168-171.

[9] Torget, Seeds of Empire, 184.

[10] McDonald, José Antonio Navarro, 118.

[11] McDonald, José Antonio Navarro, 250-251.

[12] McDonald, José Antonio Navarro, 250-251.

[13] McDonald, José Antonio Navarro, 261.

[14] McDonald, José Antonio Navarro, 278.

- African Americans and Race relations in San Antonio Texas, 1867-1937, Kenneth Mason, Taylor and Francis Publishers, 1998 Studies in African American History and Culture Series

-

Ángel Navarro, father of José Antonio Navarro, was a worldly man of 44 when he described his journey from the Mediteranean island of Corsica in a letter to the Spanish Governor of Texas, Manuel Muñoz, in 1792:

“I am from the island of Corisca, province of Ajaccio and I left there in the year 1762. I left my parents without their permission at the age of thirteen or fourteen and embarked for Genoa. After a while I embarked for Barcelona, and from there to Cadiz, always seeking to serve various persons to earn my keep…”

When Ángel Navarro (most likely known as Angelu in his homeland) was born in the late 1840s, the Mediteranean island of Corsica had been ruled by the Republic of Genoa for centuries. Corsica proclaimed its independence from the Genoese government in 1755 but it was short-lived as Genoa, and ultimately, France would govern the island.

Navarro traveled from his home in Ajaccio on the western edge of Corsica to Genoa, then to Barcelona, and finally to Cadiz on the North Atlantic side of the Iberian Peninsula. Cadiz was the primary port for ships sailing to and from the Americas when Navarro arrived in Spain. It was here that Navarro likely learned about the merchant trade and opportunities that existed in New Spain.

Veracruz and Vallecillo

The twenty year-old Navarro made the journey to New Spain around 1768. The Port of Veracruz was likely where he landed. If that is the case, he would have disembarked at San Juan de Ulua, the island fortress at which his son, José Antonio, would later be imprisoned.

A silver strike in 1766 attracted many fortune seekers to the desert north of Monterrey in the province of Nuevo Leon.

“…and it was thus that I came to these kingdoms. I arrived with the obligation of finding employment with Don Juan Antonio Agustin in the Mining district of Vallecillo. I served him for about eight years…”

Vallecillo was often times hostile, the area’s settlements were vulnerable to raids, highway robberies and corruption. The mines in the region were dependent upon the labor of indigenous people who were brutally exploited in order to hastily extract silver. Ángel likely served Juan Antonio Agustín as an apprentice of the merchantile trade from around 1770 until 1778. The two sold manufactured goods such as cloth and housewares at trade centers where they were otherwise unavailable.

San Antonío de Béxar

Ángel first appears in the 1779 Bexar census and is identified as a merchant. Ángel likely bought and sold goods that would be difficult to acquire in Spanish Texas such as cloth and crockery. According to census records he was an active participant in the slave trade at this time.

By 1792 Ángel married María Gertrudis Joséfa Ruiz y Pena who was from a prominent family in San Antonio. The couple had seven living children. José Antonio was the third child. The Navarro family home was located on what is now the corner of W. Commerce and N. Flores Streets.

“from there I came here as a merchant to this Presidio of San Antonio de Bexar. I maintained myself six years as a single man and nine years, to the present year, as a married man with two children that God has given me.”

Bexareños (residents of San Antonio de Béxar) elected Ángel as alcalde (mayor), four times as assistant alcalde and numerous times as an alderman.

On October 31, 1808 Ángel Navarro died at the age of fifty-eight. He was the first to be buried west of San Pedro Creek, in Campo Santo Cemetery which is in the present-day area of Santa Rosa Hospital and Milam Park. Ángel had helped fund the cemetery’s construction the previous year.

The Navarro Legacy in Texas

Ángel and his wife, María Gertrudis, raised seven children to adulthood, José Ángel, María Joséfa, José Antonio, José Francisco, María Antonia, José Eugenio, and Luciano. According to José Antonio, his father, "by means of commerce was able to maintain the family in good circumstances and educate his children."

Ángel’s sons, daughters and grandchildren played active roles in the development of Texas in the coming decades. Their accomplishments as elected officials in civic and state government, the military, and education demonstrate the beginnings of Tejano integration into America.