Text by Andy Rhodes, photos by Patrick Hughey

Four years before the famous battles at the Alamo and San Jacinto, a little-known skirmish occurred at the mouth of the Trinity River east of Houston. The location has been called the “birthplace of the Texas Revolution” because the events that occurred here in 1832 kindled the drive for independence.

A fort—constructed by Mexican convicts in 1830 and named Anahuac to honor the ancient home of the Aztecs—was intended to protect Mexico as it enforced a new law decreasing further Anglo-American colonization. In 1832, William B. Travis and his law partner Patrick C. Jack antagonized Mexican Col. Juan Bradburn by organizing a civil militia and attempting to recover escaped slaves. These conflicts resulted in Travis’ and Jack’s imprisonment at Fort Anahuac, leading to armed confrontation on June 10. The escalated tensions simmered for years before coming to a head at the legendary battles for independence in 1835–36.

“Anahuac brought together strong personalities with differing ideas on their liberties and their loyalties,” reports THC Historical Markers Program Coordinator Bob Brinkman. “As Texas Revolution eyewitness Creed Taylor later recalled, ‘The spirit of revolt began to flare up everywhere and was soon at white heat’.”

Fort Anahuac and other sites that played a significant yet underappreciated role in the Texas Revolution are peppered throughout the Texas Historical Commission’s Texas Independence Trail Region. Many of these locations are ideal day trips for area residents in search of an escape from the city for an afternoon of learning and exploring.

At Fort Anahuac Park, visitors can spend an hour or two strolling the peaceful grounds reading several THC historical markers, including the official William B. Travis marker. Dozens of concrete strips outline the approximate location of the multi-sided Fort Anahuac, anchored in the center by a 1936 Centennial Marker.

Overlooking a dramatic bluff at the mouth of the Trinity River, the park also features an extensive pier with elevated viewing stands that draw birders and several acres of natural areas for campers, anglers, and hikers. Sharp-eyed visitors may also catch a glimpse of Fort Anahuac itself: portions of the original brick that comprised the seven-foot-thick walls are scattered just below the bluff’s surface (please leave them in place).

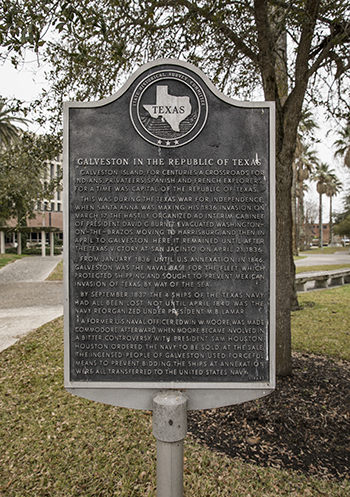

About 45 miles southeast of Houston is Galveston, known for its historic buildings and panoramic beaches. But did you know Galveston played a role in Texas’ independence?

On March 17, 1836, the hastily organized and interim cabinet of President David G. Burnet evacuated Washington-on-the-Brazos at the approach of Mexican Gen. Santa Anna’s army, eventually moving the Texians’ seat of government to Galveston. It remained there until after the Texas victory at San Jacinto on April 21.

“It’s true that Galveston briefly served as the capital of the republic,” says Dwayne Jones, executive director of the Galveston Historical Foundation. “That’s pretty important because this was the largest city at the time. Immigration was picking up, and people from across Europe were arriving and taking their first steps on the soil of Galveston Island. It’s exciting to think about—they were leaving their home countries and starting new lives right here.”

The harbor’s significance was recognized as early as 1825, when Stephen F. Austin petitioned the Mexican government to establish a port. From January 1836 until U.S. annexation in 1846, Galveston was the naval base for the fleet, which protected shipping and sought to prevent Mexican invasion of Texas by sea.

Galveston’s distinctive 19th-century heritage is featured across the island on nearly 100 THC markers, including a dozen in the courtyard of the Galveston County Courthouse. Be sure to look for the oversized 1963 tourist marker for Galveston Island at the entry to the Port Bolivar Ferry.

Texas Revolution-era treasures await at Galveston’s Bryan Museum. Most significant is the short sword that was used by Texian soldier Joel Robison when he helped capture Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto. The museum features several other artifacts from the Republic of Texas period along with rare documents in its extensive archives, including Santa Anna’s order book from the 1835–36 Texas Campaign.

For those who venture to see the marker at the ferry, it’s worth boarding the boat to Bolivar for another distinctive heritage experience. After about 20 minutes of viewing dolphins and sea birds from atop the ferry deck, disembark onto Bolivar Peninsula and travel a mile east to Fort Travis Seashore Park.

Visitors are immediately greeted by several enormous concrete battery fortifications dating to 1898. The stately structures harken back to an era when the U.S. military fortified the gulf coast in defense of adversaries before and during World War I.

The site’s early history is tied to the Texas Revolution era. In 1836, soon after Texas declared independence from Mexico, Republic of Texas President David Burnet ordered a fort to be constructed across the bay. The octagonal earth and timber fortification armed with six and 12-pound gun mounts was later named Fort Travis in honor of William B. Travis. Later relocated to its current site and renamed Fort Green, the triangular fortification was most likely destroyed by Confederate troops when they surrendered Galveston and the surrounding area to Union troops.

“The location of Fort Travis and its two batteries corresponds with the original function of the fort,” Brinkman says. “It’s the most complete concentration of coastal artillery batteries on the Texas Gulf Coast.”

The batteries are mostly off-limits for visitors, although they can climb the encompassing earthen hillsides and peer through the chain-link fence or take photos of the imposing poured-concrete structures. The site is listed in the National Register of Historic Places

and features a THC marker.

For those unable to catch the Port Bolivar Ferry, consider riding across the Houston Ship Channel on the Lynchburg Ferry. This modern vessel’s route has ties to the 1820s, when Nathaniel Lynch established a ferry service nearby. Lynch, one of Stephen F. Austin’s first colonists, was granted exclusive privilege to operate the ferry by the San Felipe Ayuntamiento (governing council).

Lynch passed away in 1837, but his family continued to operate the ferry service until 1848. It outlasted fires and storms, and evolved from a cable-based operation to the modern 85-ton diesel-powered boats. The THC marker commemorating this historic route is somewhat challenging to find (on the northern end of the ferry crossing in the midst of a surreal industrial scene), but it’s a fascinating diversion and serves as a reminder of the area’s growth over the past two centuries.

From the Lynchburg Ferry marker, visitors can see the San Jacinto Monument looming over the bay. Although San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site is not an unknown revolution location, it contains several markers and monuments that are often overlooked by visitors entering and exiting the 570-foot-tall monument.

Just west of the towering column is a small graveyard with headstones honoring many soldiers who perished at the Battle of San Jacinto. A THC historical marker commemorates Lorenzo de Zavala, vice president of the Republic of Texas, who devoted his life to fighting against tyranny. Several other stone monuments dating to the early 1900s represent the State of Texas’ dedication to erecting physical reminders of the heroes who helped forge the Lone Star State.

“Most Texans can rattle off the Alamo, Goliad, and San Jacinto, and those are certainly big chapters in the story of the Texas Revolution,” Brinkman remarks. “But look in between and beyond for important factors like settlement, family, economics, and politics. You’ll be rewarded by a deeper understanding and a richer experience of a seminal period of history with human scale and global impact.”